Making a fast RL env in C with pufferlib

Goal for this article

We ask ourselves: can Reinforcement Learning solve Common Pool Resource (CPR) problems? To answer that, we will make a fast environment in C using pufferlib, and train PPO on it. We want to know if the agents deplete the resource or manage to find a optimal balance.

Common Pool Resource (CPR)

A common pool resource is a type of good that faces problems of overuse because it is limited. It typically consists of a core resource, which defines the stock variable, while providing a limited quantity of extractable units, which defines the flow variable. The core resource must be protected to ensure sustainable exploitation, while the flow variable can be harvested. source

Pufferlib

Reinforcement Learning is currently cursed with super slow environments and algorithms, with many hyperparameters which leads to a ton of bad research. Indeed, it is close to impossible to benchmark and compare solutions when you need to run hyperparam sweeps in high dimensions, when each run takes days.

Pufferlib is an open sourced project aiming at fixing that. Mainly, they provide fast envs running at millions of steps per second, enabling you to run sweeps much faster. Additionally, they are building faster algo implementation and faster and better hyperparameter search solutions.

All of this unlocks good research. Everyone can contribute by writing new envs for specific research usecases. We will fork their repo and take inspiration from their basic C envs to make our own.

Setup

Fork the repo. You can use the 2.0 branch (at the date of this writing), or dev branch, but be aware it might be broken. I don’t have a GPU, so you won’t be able to use puffertank (their container, which actually makes it easier to work with). You want to interface your C env with python, and I find python 3.10.12 working just fine. Create a virtual environment to make things easier.

You’ll need to install a lot of dependencies, and currently pufferlib doesn’t make it super easy to use without a GPU. You can run their demo file with

python demo.py --env puffer_connect4 --train.device cpu

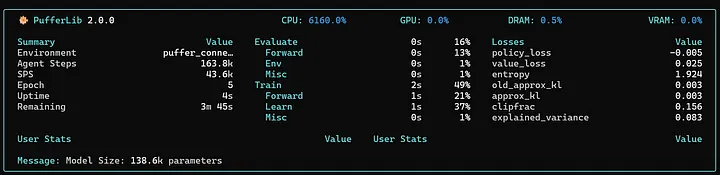

Or any other env really, you can just look at their documentation here. This should be showing the puffer console, and starts training:

Once this runs, you should be fine. You want to make a new C env inside their pufferlib/ocean/ folder. Create a new one, I’ll name mine cpr/. You want a .h and .c file. The .c file will mainly be for testing because in the end, you’ll interface it with cython through a .pyx and .py file.

You can start by reading or copy / pasting their squared env files, or snake (a bit more advanced).

Basic C grid multi agent env

The C environment is pretty straightforward. Let’s look at our .h file. Let’s describe the environment first.

CPR Environment

This will be a grid-based world, with multiple agents. The agents actions are 5 possible moves: Up, Down, Right, Left, Nothing.

The agents have partial observations of the environment, with a certain radius, thus the observations must be computed for a 2radius+1 by 2radius+1 grid around each agent.

1 step of the environment means stepping every agent with their action passed into a buffer. Agent turn order is currently not random and each agent is stepped one after another, so we easily avoid collision issues.

There is food in this world. Two types of foods:

- Grey food: an agent collects the food whenever it steps onto the same cell as a grey food

- Yellow food: this food requires two agents to stand next to it (only the 4 adjacent squares, no diagonal) - then gets collected

The food respawn mechanism is roughly as follow:

- The food can only respawn next to another similar food-type

- Each step, for every food currently on the map, there is a probability of a new food spawning next to it (8 adjacent squares - diagonals too). The probability is defined for each type of food

- There is a very low probability for a new food to spawn randomly in the map, to cope with complete resource depletion

The agents gets rewarded:

- Each time they collect a food (different reward for different types)

- Each step (usually a small, negative reward)

The goal of the agents is to maximize the expected reward over the long run. We expect the agents to learn how to navigate and collect each type of food, and, hopefully, observe what happens when agents learn to deplete the food. Intuitively, we can think that the optimal gameplay for the agents is to leave some food on the table to they can regenerate, but we’ll see that solving this is much harder than we thought. Let’s now describe the code

Basic RL environment structure

We need to follow the standards for an environment in RL. Therefore, we need at least:

- A reset function, which resets the environment in a starting state

- A step function, which steps the entire environment with the actions

- A render function

Macros

Usefull macros are basically the ids for entity types. I recommand putting Agents or any entities which need to be discerned at the end, so this can help code after. I also separate obstacles from non obstacles, usefull in small envs. I also have macros related to bitmasking, but this can be avoided, see below for an explanation.

#define EMPTY 0

#define NORMAL_FOOD 1

#define INTERACTIVE_FOOD 2

// Anything above Wall should be obstacles

#define WALL 3

#define AGENTS 4

#define LOG_BUFFER_SIZE 8192

#define SET_BIT(arr, i) (arr[(i) / 8] |= (1 << ((i) % 8)))

#define CLEAR_BIT(arr, i) (arr[(i) / 8] &= ~(1 << ((i) % 8)))

#define CHECK_BIT(arr, i) (arr[(i) / 8] & (1 << ((i) % 8)))

#define min(a, b) ((a) < (b) ? (a) : (b))

#define REWARD_20_HP -0

#define REWARD_80_HP 0

#define REWARD_DEATH -1.0f

#define LOG_SCORE_REWARD_SMALL 0.1f

#define LOG_SCORE_REWARD_MEDIUM 0.2f

#define LOG_SCORE_REWARD_MOVE - 0.0

#define LOG_SCORE_REWARD_DEATH -1

#define HP_REWARD_FOOD_MEDIUM 50

#define HP_REWARD_FOOD_SMALL 20

#define HP_LOSS_PER_STEP 1

#define MAX_HP 100

Logs

The first chunk of the .h file is mainly for logging. We want to be able to add and clear logs. What you put in your logs is up to you, but at a minimum I recommand you have some score metric. The reason you want to name is score is because this is the default metric that the sweep algorithms will look for to maximize, although you could name it whatever and change this setting in the config files afterwards.

typedef struct Log Log;

struct Log {

float perf;

float score;

float episode_return;

float moves;

float food_nb;

float alive_steps;

float n;

};

Agent

We define an Agent struct. It has id, row and column, very simple

typedef struct Agent Agent;

struct Agent {

int r;

int c;

int id;

float hp;

int direction;

};

FoodList

We make a struct for FoodList. This is for optimization. At some point, we want to iterate through the foods on the map, so we can spawn some more food next to it. Without a FoodList somewhere, we would need to iterate over the entire grid. This reduces a bit computation, while slightly increasing memory usage. We directly give it the flattened indexes of the grid since we want to easily interate over it.

typedef struct FoodList FoodList;

struct FoodList {

int *indexes; // Grid flattened index positions

int size;

};

CPR env struct

This is the basic structure of the environment. It has everything you need. The grid is basically just a list of integers, each representing one entity. The cool stuff to note here is how we manage the observations, rewards, actions and terminals. Those are all buffers we directly write into. This will be helpfull in speeding up the env when we use it from python afterwards.

typedef struct CCpr CCpr;

struct CCpr {

Renderer* client;

int width;

int height;

int num_agents;

int vision;

int vision_window;

int obs_size;

int tick;

float reward_food;

float reward_move;

float interactive_food_reward;

unsigned char *grid;

unsigned char *observations;

int *actions;

float *rewards;

unsigned char *terminals;

unsigned char *truncations;

unsigned char *masks;

Agent *agents;

Log log;

Log* agent_logs;

uint8_t *interactive_food_agent_count;

FoodList *foods;

float food_base_spawn_rate;

};

The other interesting thing to notice is the interactive_food_agent_count. Interactive food require at least 2 agents next to it to be collected. When an agent move next to an interactive food, we use bitmasking (see here) to check wether another agent is next to it. This is not required, as we could iterate over the adjacent cells of an interactive food once an agent stands next to it, to see whether or not there is another agent. With bitmasking, however, we directly index on the food, removing any need of iteration, while keeping very little memory overhead.

Next, we have our allocation mechanisms. The allocate_ccpr is only used by the .c file because we need to instanciate the observation, rewards, terminals, etc, whereas when using the env directly from Python we will have them already created. You can look at the code here

Handling of foods

Nothing really special here, but we need functions to add, remove, and spawn new foods. Here is the code for the latest.

void spawn_foods(CCpr *env) {

// After each step, check existing foods and spawns new food in the

// neighborhood Iterates over food_list for efficiency instead of the entire

// grid.

FoodList *foods = env->foods;

int original_size = foods->size;

for (int i = 0; i < original_size; i++) {

int idx = foods->indexes[i];

int offset = idx - env->width - 1; // Food spawn in 1 radius

int r = offset / env->width;

int c = offset % env->width;

for (int ri = 0; ri < 3; ri++) {

for (int ci = 0; ci < 3; ci++) {

int grid_idx = grid_index(env, (r + ri), (c + ci));

if (env->grid[grid_idx] != EMPTY) {

continue;

}

switch (env->grid[idx]) {

// %Chance spawning new food

case NORMAL_FOOD:

if ((rand() / (double)RAND_MAX) < env->food_base_spawn_rate) {

add_food(env, grid_idx, env->grid[idx]);

}

break;

case INTERACTIVE_FOOD:

if ((rand() / (double)RAND_MAX) <

(env->food_base_spawn_rate / 10.0)) {

add_food(env, grid_idx, env->grid[idx]);

}

break;

}

}

}

}

}

What’s important here is that we use our FoodList to iterate over the foods. This reduce iterations from height*width (iterating over the entire grid) to n, with n being the current number of foods in the grid.

Observations

These are just a grid centered at each agent, parametrized by the vision variable. Nothing fancy here.

void compute_observations(CCpr *env) {

// For full obs

// memcpy(env->observations, env->grid,

// env->width * env->height * sizeof(unsigned char));

// return;

// For partial obs

for (int i = 0; i < env->num_agents; i++) {

Agent *agent = &env->agents[i];

// env->observations[env->vision_window*env->vision_window + i*env->obs_size] = agent->hp;

if (agent->hp == 0) {

continue;

}

int obs_offset = i * env->obs_size;

int r_offset = agent->r - env->vision;

int c_offset = agent->c - env->vision;

for (int r = 0; r < 2 * env->vision + 1; r++) {

for (int c = 0; c < 2 * env->vision + 1; c++) {

int grid_idx = (r_offset + r) * env->width + c_offset + c;

int obs_idx = obs_offset + r * env->vision_window + c;

env->observations[obs_idx] = env->grid[grid_idx];

}

}

}

}

Reset function

The trick here is to put walls inside the grid with radius width, so the observations can’t go over the grid, and the agents neither. This obviously removes a big portion of the grid if the observations are big, but it just ends up being static cells, so just a bit of memory, and make things much easier to handle. Note that this could be handled by memsets.

void c_reset(CCpr *env) {

env->tick = 0;

memset(env->agent_logs, 0, env->num_agents * sizeof(Log));

env->log = (Log){0};

env->foods->size = 0;

memset(env->foods->indexes, 0, env->width * env->height * sizeof(int));

// make_grid_from_scratch(env);

memcpy(env->grid, grid_32_32_3v, env->width * env->height * sizeof(unsigned char));

for (int i = 0; i < env->num_agents; i++) {

spawn_agent(env, i);

}

init_foods(env);

memset(env->observations, 0, env->num_agents * env->obs_size * sizeof(unsigned char));

//memset(env->truncations, 0, env->num_agents * sizeof(unsigned char));

memset(env->terminals, 0, env->num_agents * sizeof(unsigned char));

memset(env->masks, 1, env->num_agents * sizeof(unsigned char));

compute_observations(env);

}

Step function

We first have the main step function, very basic

void c_step(CCpr *env) {

env->tick++;

memset(env->rewards, 0, env->num_agents * sizeof(float));

memset(env->interactive_food_agent_count, 0,

(env->width * env->height + 7) / 8);

for (int i = 0; i < env->num_agents; i++) {

if (env->agents[i].hp == 0) {

env->masks[i] = 0;

clear_agent(env, i);

continue;

}

step_agent(env, i);

remove_hp(env, i, HP_LOSS_PER_STEP);

}

spawn_foods(env);

//We loop again here because in the future an entity might have attacked an agent in the process

int alive_agents = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < env->num_agents; i++) {

if (env->agents[i].hp > 0) {

env->agent_logs[i].alive_steps += 1;

alive_agents += 1;

if (env->agents[i].hp < 20) {

reward_agent(env, i, REWARD_20_HP);

env->agent_logs[i].score += REWARD_20_HP;

} else if (env->agents[i].hp > 80) {

reward_agent(env, i, REWARD_80_HP);

env->agent_logs[i].score += REWARD_80_HP;

}

}

}

env->log.food_nb = env->foods->size;

compute_observations(env);

if (alive_agents == 0 || env->tick > 1000) {

c_reset(env);

if (alive_agents == 0) {

memset(env->terminals, 1, env->num_agents * sizeof(unsigned char));

}

}

}

Most of the logic is therefore in the step_agent function, as you can see below.

void step_agent(CCpr *env, int i) {

Agent *agent = &env->agents[i];

int action = env->actions[i];

int dr = 0;

int dc = 0;

switch (action) {

case 0:

dr = -1;

agent->direction = 3;

break; // UP

case 1:

dr = 1;

agent->direction = 1;

break; // DOWN

case 2:

dc = -1;

agent->direction = 2;

break; // LEFT

case 3:

dc = 1;

agent->direction = 0;

break; // RIGHT

case 4:

return; // No moves

}

env->agent_logs[i].moves += 1;

// Get next row and column

int next_r = agent->r + dr;

int next_c = agent->c + dc;

int prev_grid_idx = grid_index(env, agent->r, agent->c);

int next_grid_idx = env->width * next_r + next_c;

int tile = env->grid[next_grid_idx];

// Anything above should be obstacle

// In this case the agent position does not change

// We still have some checks to perform

if (tile >= INTERACTIVE_FOOD) {

env->agent_logs[i].score += LOG_SCORE_REWARD_MOVE;

reward_agent(env, i, env->reward_move);

next_r = agent->r;

next_c = agent->c;

next_grid_idx = env->width * next_r + next_c;

tile = env->grid[next_grid_idx];

}

switch (tile) {

case NORMAL_FOOD:

reward_agent(env, i, env->reward_food);

env->agent_logs[i].score += LOG_SCORE_REWARD_SMALL;

add_hp(env, i, HP_REWARD_FOOD_SMALL);

remove_food(env, next_grid_idx);

break;

case EMPTY:

env->agent_logs[i].score += LOG_SCORE_REWARD_MOVE;

reward_agent(env, i, env->reward_move);

break;

}

// Interactive food logic

int neighboors[4] = {

grid_index(env, next_r - 1, next_c), // Up

grid_index(env, next_r + 1, next_c), // Down

grid_index(env, next_r, next_c + 1), // Right

grid_index(env, next_r, next_c - 1) // Left

};

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

int grid_idx = neighboors[j];

// If neighbooring grid tile is interactive food

if (env->grid[grid_idx] == INTERACTIVE_FOOD) {

// If was already marked as "ready to collect"

if (CHECK_BIT(env->interactive_food_agent_count, grid_idx)) {

reward_agents_near(env, grid_idx);

} else {

// First agent detected

SET_BIT(env->interactive_food_agent_count, grid_idx);

}

}

}

// update the grid tiles values

int agent_tile = get_agent_tile_from_id(agent->id);

env->grid[prev_grid_idx] = EMPTY;

env->grid[next_grid_idx] = agent_tile;

agent->r = next_r;

agent->c = next_c;

return;

}

Nothing really fancy here, it’s actually pretty simple. We get the delta from the action for each agent, we compute the next grid_cell, and then we basically have a list of checks to perform based on what’s on that cell, and what’s next to it.

As said above, in the interactive food logic part, you could get rid of the use of bitmasking, and instead iterate over the adjacent cells of the interactive food.

Rendering

Rendering here is done using raylib. You can see the code in the github repo, the current rendering is the bare minimum, and I’m not a big fan of UI design (as you can see from the horrible looks of the rendered env), so I’ll leave this up to you.

Testing the C env

Well played ! You now should have a working env in C. You can create a .c file, make your env, call your allocate and reset functions and render it. Compile your code and you’re good to go. For a basic .c file structure, look into my repo here

Interfacing with Cython and port to Python

Cython

It’s now time to port this code to python ! First, you need to make a .pyx file for cython, and expose your structs. There is absolutely no logic in this, so i’ll leave it up to you to look on the repo how it’s done. It’s just boring code, really.

Python

Here it’s the same. A couple of things to be said though. You need to inherit from pufferlib.PufferEnv, and respect the structure. This is a very similar structure to anything you might have seen with any other RL libraries such as gymnasium or pettingzoo. The thing is to make sure your env can be vectorized, so make sure you give it lists of widths, agents, and anything you might want to have different in every env as a list. It needs to match your Cython def too, obviously.

The code is boilerplate, mainly you want to implement the init, reset, step, render and close functions, which will mostly just call the cython init, reset, step, render and close functions, which will in turn mostly just call the same C functions…

Making your env usable with pufferlib

You can already use your env just as is, as long as you compile things correctly. If you want to use it with pufferlib, you want to add your environment in the ocean/environment.py file, in the MAKE_FNS part.

Add your env next to the other lazy_imports (if you’ve made your env in ocean as a C env).

Second thing is to add it to the setup.py file to the extension paths (see here).

After that, you can compile using

python setup.py build_ext --inplace

You’re done ! Your env is compiled and usable with pufferlib.

Training

I’ll leave the technical details here. If you don’t want to bother too much, with pufferlib, you can use the default policies and train your env with

python demo.py --env cpr --mode train

Make sure to create a .ini config file in config/ocean/. Take example on the others to setup which model, hyperparams and timestemps you want to train for.

Here is mine after 300m steps of training a basic RNN using PPO (click on the image):

Conclusion

We clearly see that the agents end up depleting the food completely. There are a couple directions to solve for that, namely:

- Train for longer times

- Perform sweeps of hyperparams

- Improve the environment to include better incentives

I’m not sure any of them would be fixing the issue, but I’m going for the third, and see you in the next update!

This was a quick introduction on how to make cool, fast environments with pufferlib. Don’t forget to star the pufferlib repo if you find that cool and want to contribute, you’re welcome!